This article was written all the way back in the Spring of 2011 during a business trip to NYC.

Back to the west wall of the Mary Boone Gallery in Chelsea, New York City’s trendy art gallery enclave, my spine is straight, my chin is tucked and my eyes softly focused on a slight Asian man dressed in white, monk-like attire who is on down on his knees, slowly circling a cone-shaped pile of salt. Of all the things to do in New York, I’m not exactly sure why I skipped the collection at the Whitney Museum or taking in a Broadway show to instead cab across town on what felt like a mission to witness the knee-bent artist, Terence Koh, circumnavigate a 24-foot by eight-foot mound of rocky solar salt, something he’s been at eight hours a day, five days a week, for the last five weeks. All I know is that when I read of the performance art exhibit on my first pass through the city, I could hardly wait to get down here and check it out.

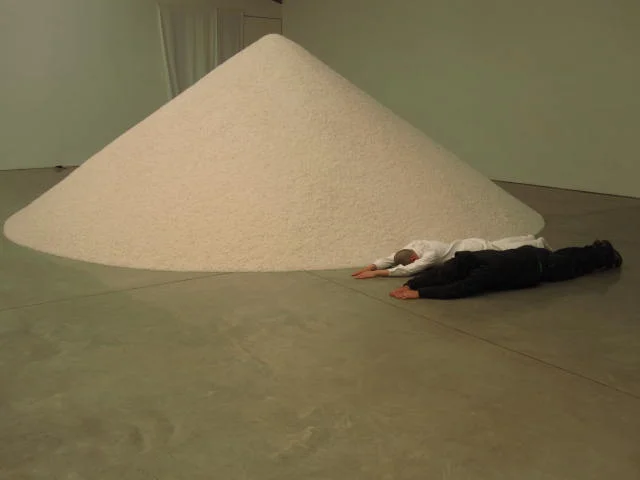

“Nothingtoodo”, the title of Mr. Koh’s, er uh production, has an exceptionally monotonous, meditative feel to it, and quietly observing it all up close has me feeling strangely peaceful. According to the NY Times write up, “This is performance art reduced to a bare and relentless rite in a space that has been stripped down to a kind of Temple… the monumental mound of salt – a preservative and curative that can also inflame open wounds – conjures up altars and offerings, as well as pain and healing.” I sit for a good hour in the bright, white-washed space, listening to the calming rhythm of two bony knees skimming the glossy concrete floor, like the sound of waves lapping at the shoreline of the sea of samsara. The performer himself looks to be in a meditative posture, hands not hanging limp but rather filled with relaxed energy, appearing as an artist of the martial variety. At times he pauses mid–shuffle and rests, mindfully retracting his form in folding-human-director’s-chair fashion, and then reopens, prostrating himself across the gallery floor.

There is an austerity to the room’s happenings (or lack of happenings), an ascetic bluntness, recalling the quiet rest and contemplation of secluded retreat. Every slight occurrence – the whoosh of the curtain announcing a new observer, a shift in the artist’s crawling pace, a muting of the room’s light due to a passing cloud – alters the room’s energy ever so slightly. Akin to sitting meditation, when not much is occurring in your outer experience, the subtle becomes very, very significant.

When it comes to critiquing a piece of artwork, I personally have two distinct categories– I either like it, or I don’t. Art is the life of life, until someone elevates it – or rather debases it – to the level of snobbery, stimulating the intellectual mind to create unneeded complexity and flooding the brain with insignificant possibilities and potential. While living in San Francisco, I ran into the friend of a local artist in line at a burrito place in The Mission, where we struck up a conversation about his comrade’s up-coming show. “One thing I can say about James,” the man offered, looking me dead in the eye, “is that he is a very IMPORTANT artist”. I found this funny, considering James was a cool guy and all, but most of his works of which I was familiar were paintings of cats. Say what you will about art, and sometimes way too much is said, as soon as you start calling it “IMPORTANT”, I find you’ve revealed yourself as someone who perhaps doesn’t know what they’re talking about.

Recalling my burrito buddy’s critique, I don’t find one piece of artwork any more “Important” than another. Every act of creation is important in that it is That person’s truthful statement, often requiring a degree of effort, imagination and courage, even and especially the crayon drawing of a three-year old. Most of life is in fact designed to be straightforward and enjoyable, but too often people fail to see the forest for the trees, turning it into a complex, boring and arduous act. Maybe Picasso crafting ephemeral arrangements of papier collés into paradigm-shattering guitars is important, MAYBE, but that’s where I draw the line. A waxy, wiggly, blue line, in Crayola’s Robin’s egg blue, to be exact.

Just before leaving New York, I later stop briefly at MOMA, the Museum of Modern Art, to see the Warhol short film exhibit. “Art is what you can get away with,” Andy Warhol once said, the spirit of this truth displayed now in Terrence Koh’s work, who took it to heart and has done pretty well for himself. Although this work I truly DO like, and after observing the salt and the crawling man and the ever-shifting audience for an extended period, realize that part of my liking of it includes the reactions of the folks viewing the exhibit as much as its main performer. “I think everybody should like everybody,” I hear Andy Warhol say again, one of his quotes which, from such a famous artisté, strikes me as pleasant and hearty, like a painting of a can of Campbell’s Onion Soup. And it occurs to me that we’re all achieving this, in our own quiet, creative and collective way – Mr. Koh, myself, the kid in the fluorescent orange ski cap, the arty, urban Mom with baby and stroller in tow, the beautiful, black-skinned Indian girl and her thin, white Duke of a boyfriend, and even a woman with her yipping little dog.