Along with my friend Tara White, I helped facilitate a Medicine Wheel Ceremony this past weekend for a great group in Richmond, Illinois, a pastoral village Northwest of Chicago. Deepening my own learning of the Medicine Wheel’s workings, I’ve come to understand these stone monuments or sacred hoops to be springboards of power, places of religious, ritual or healing forces that link up the energies of the Universe.

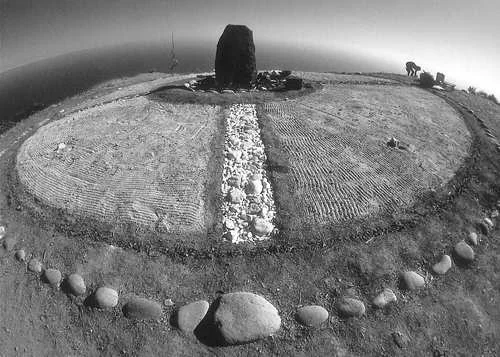

The 20,000 wheels that existed on this continent before the European people immigrated here were ceremonial centers of culture, astrological laboratories and places where people would come to pray, meditate, contemplate, strengthen their connection to nature, and come to a higher degree of understanding of themselves and their relationship with all of creation. Although much of the Wheels’ origins are shrouded in mystery, they were and continue to be constructed by laying stones in particular patterns on the ground oriented to the Four Directions, often a symbol or template of the enlightened mind.

Native people think of plants, animals and minerals as having certain powers, and they often refer to these other beings as totems, or as our relations. For human beings seeking a right relationship with the rest of creation, the sacred Medicine Wheel can help bring a sense of balance, restoring harmony. Medicine Wheels were usually placed on areas where the energy of the earth could be strongly felt, and their use in Ceremony strengthened their Ju Ju. Consequently, Medicine Wheel areas became what people now call vortexes: places of intense earth energy and reinvigoration. The new areas where Medicine Wheels have been built are serving the same function, including Tara’s backyard layout.

Surrounded by knotty old Oaks, just being outside on the grass in the April sunshine provided us uplift. And mediating to the sound of singing Rock Wrens and Eastern Whip-poor-wills brought a collective inner and outer cheer to all. Considering neither Medicine Wheels nor Journeying have been practices that have played a major parts in my own learning or teachings, the day flowed melodiously, as I personally employed the Helpful Hints For Journeying provided by Tara, specifically #4: “Remember the times you have observed children approaching a new experience with curiosity, awe and wonder, bringing their innocence and trust to the exploration. Tap your own curiosity and sense of wonder.”

Many thanks to Tara, Rick, Roxanne, and others, especially fire tender Shadow Mountain, who passed on some great teachings about the land. I’m excited to explore further summer gatherings around the Medicine Wheel in the coming months.